About

Hi all! I’m Mae, and this is my blog! So far, I use it for short fiction and analytical/philosophical essays!

Check out some of my friends’ blogs!

For as long as I’ve been using the internet, direct messaging, video-and-voice chat, and group messaging have predominantly been the domain of closed services.

I’ve used Facebook Messenger, Skype, Discord, and probably a handful of other platforms, and every one of them has gotten worse and worse until a critical mass of my friends got annoyed enough to switch to the next.

Well, that process has been progressing with the most recently adopted option - Discord - and I’m fed up. It’s time to break the cycle. A lot of the internet is moving towards federated services, and it’s time for the messaging space to move with it!

What’s XMPP?

XMPP is a messaging protocol that’s been around for nearly 30 years.

It’s an open standard that accepts updates by committee, and it’s been used all over the internet in places you probably wouldn’t expect: Google Talk was built on it, Facebook Messenger was compatible with it from 2010 to 2014, Skype was in 2011 - and according to its Wikipedia article, AOL was compatible with it in 2008, and both Origin and PlayStation use it as their messaging protocols (though they presumably don’t allow users to connect to external servers with it).

Speaking of connecting to other servers, that’s one of the great things about XMPP: It’s federated. Your account lives on a specific server, but that account can connect to other accounts and group chats on other servers as well! No one company runs all of XMPP, and there’s no central authority controlling who can use it or what they can say or do.

Its nature as an open standard also means that there’s no one official client! There are a variety of clients (most of which are open source) for a variety of platforms, meaning that if you don’t like decisions one has made, you can switch to another!

Why Should I Care?

Alright, so this thing exists. Why should you care about it at all?

Well, to start with, everything about XMPP is open. An open standard means anyone can make a client or server without fear of legal takedowns, and that combined with open-source clients means the community decides what features are or are not added. Open federation means you can communicate with your friends on different servers without a hitch.

Closed services like Discord can start out as good as they want, but their primary motivator is making money, and that means that no matter how good their creators’ intentions, they will always inevitably get worse. This doesn’t and can’t happen with open frameworks like XMPP.

Privacy matters for messaging platforms. If you’re talking to your friends, you don’t want to have to worry about what the company that owns that platform thinks is okay to talk about—or worse, the advertizers or payment processors that keep them afloat. My conversations online should be no more the business of a random corporation than my conversations in-person.

Lastly, sovereignty matters. I’m a denizen of the internet, and have been since I was a child: My chatgroups are my home on the internet, and they should feel like home. I don’t want my conversations or friends or even just my UI messed around with by some corporation anymore than I want that corporation moving things around in my house, kicking my friends out, and threatening me with a big stick if I don’t do as they say.

On the internet, my XMPP server is my home, and I own that home. I feel safe on that home. Do you feel safe on Discord, or Messenger, or Telegram? Me neither.

What’s Bad About It?

Ok great, those are the main selling-points, what’s the catch?

Mainly, features.

XMPP has a lot of features in theory, but what matters is which features are implemented, and how widely. The answer to that depends on what server and client (mostly client) you’re using, but I’ll give an overview.

All the server software and most clients support:

- Profile pictures, notifications, emoji, etc.

- Multi-User Chats / Group chats. This, notably, does not include Discord-style servers, only group chats.

- Retrieving missed messages or message history from servers. Minor thing, but XMPP has the least-buggy implementation of this out of any platform I’ve used. Especially compared to Discord or Matrix.

- File/image sharing

- Encrypted messages

- Read receipts, replies, and mentions

- Message formatting (italics, bold, lists, etc.)

- Registering on a public server via your client

Most clients support:

- Video and Voice calling - Every client I’ve used except Gajim supports this, but Gajim is the most accessible client on Windows.

Most clients don’t yet support:

- Discord-style custom emoji - there’s an extension specification for it and some other related features, but most clients don’t support using it for custom emoji yet. Once they do, which custom emoji you can use will likely depend entirely on what emoji you have added on your client, which is nice.

- Voice messages and stickers - they’re both part of the aforementioned specification, and some clients support them, but most don’t. Gajim supports voice messages, and Movim supports voice messages and stickers.

- Discord-style guilds/servers - there’s an extension specification for it, it’s just really recent, so it’s not really implemented anywhere yet. This will probably exist in a year or so. Until then, you can still group chatrooms client-side in basically every client, there just aren’t server-defined groups of them.

Some clients will soon apparently support:

- Serverless client-to-client messaging - messaging other people peer-to-peer without a server. Apparently Gajim supports this? But I haven’t tested it yet. Either way, it’s a cool feature to look forward to.

What’s Good About It?

It Works

Current implementations are missing a few features, but XMPP has all the essential features for you to begin using it right now. Other in-the-works alternatives such as Stoat (formerly Revolt) are still missing basic features like notifications, but XMPP is fully-functional.

It’s Improving

The clients and protocol are and have been improving slowly but surely. The standards-based feature-set means that developers and users are able to talk over features before they’re implemented, instead of haphazardly adding things nobody wants, and the open protocol means that if a client makes changes you don’t like, you or someone who agrees with you can fork that client or make their own, without being in violation of terms of service like they would be for doing the same with Discord or other closed apps.

It’s Federated

Unlike both mainstream options such as Discord or Messenger and alternatives such as Signal or Stoat, XMPP’s federated nature means that you aren’t reliant on one centralized service.

If Signal’s servers are taken down and the company is attacked by national governments, you might not be able to keep using it; if Stoat runs out of funding for their servers, you might lose contact with your friends; but if your XMPP server goes down, you can move to a new one, add your contacts back, and go back to your life without much fuss.

It’s Friendly

XMPP’s protocols and interfaces are functional and relatively easy to use. They might not be quite as seamless and polished as something like Discord, but they’re a far cry from the constant security-hounding and obtuse interfaces of something like Matrix.

If I were to use one word to describe the difference in feeling between using it and XMPP, it really is “friendly”. XMPP lets me access all of my messages easily, has much better multi-account handling, and doesn’t constantly force me to use excessive security features while still leaking my data. 1 See Matrix Notes by Anarcat. 2 See also Matrix vs. XMPP by Luke Smith. Fair notice: I don’t endorse Luke Smith’s politics. His stances on technology are pretty good though.

It’s Here To Stay

XMPP has been around for nearly 30 years now, and in that time it’s survived multiple attempts to replace it with services which nobody uses anymore. AOL is dead, Skype is dead, Google Talk is dead, but XMPP lives on.

Its open nature and extensibility means that XMPP cannot ever truly be killed.

It Isn’t Just Getting Worse

The last advantage to XMPP’s nature as an open protocol primarily run on open-source software is that it isn’t vulnerable to the corrosive effects of profit incentives and monetization.

This article is being posted now because Discord is pushing age verification in order to make it seem like they’re doing something about the abuse on their platform, making it worse for the sake of appealing to payment providers and government officials. XMPP will never—can never do that. Discord adds premium-only features that should be available to all users, and then adds more that get in the way of the base usage. XMPP, again cannot and will not ever do that.

It isn’t perfect, but it’s as imperfect as it will ever be. It’s getting better, not worse.

How Do I Start?

Getting an Account

Being federated means that there isn’t one canonical place to create your XMPP account, and that means you need to choose a server.

- (Easiest for everyone) Find an open-registration server from this list, and register there.

- (If you’re a friend of mine) You can message me and ask for an account on my server, and I’ll make you one!

- (If you’re technically-inclined) You can host your own server! I recommend ejabberd.

Once you have an account, you’ll want to select a client or clients and login on them. Most clients actually support registering within the client, but there’s no convenient list of servers in them, so you still need to decide where to register first.

Choosing a Client

I’ve split these up by platform, since you’ll presumably want to use this on all of your devices.

Android

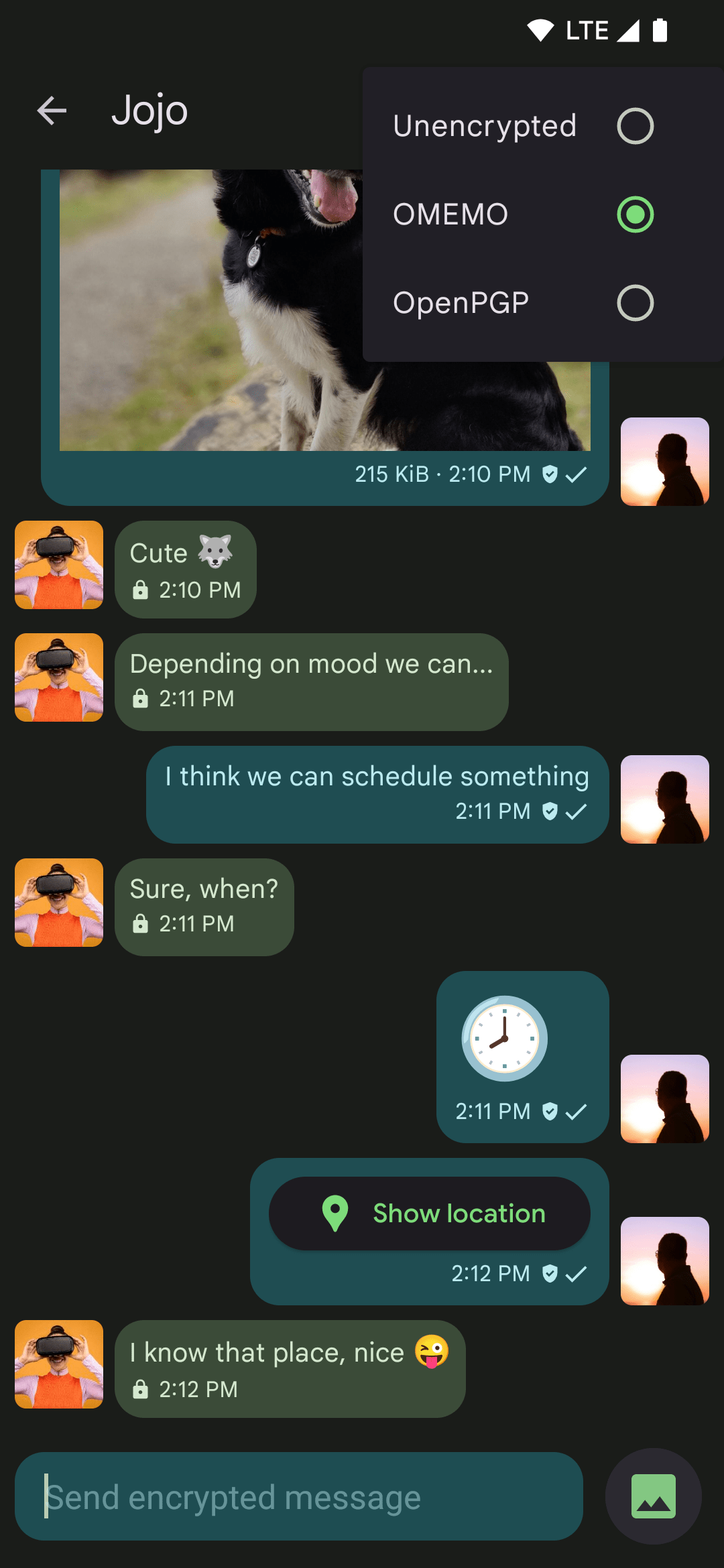

Conversations

Conversations a very good Android XMPP client, and close to the best overall native client, to boot.

The two major features it doesn’t support are message editing and workspaces (groups of chats). These aren’t usually a major problem, but it is weird that it doesn’t have them.

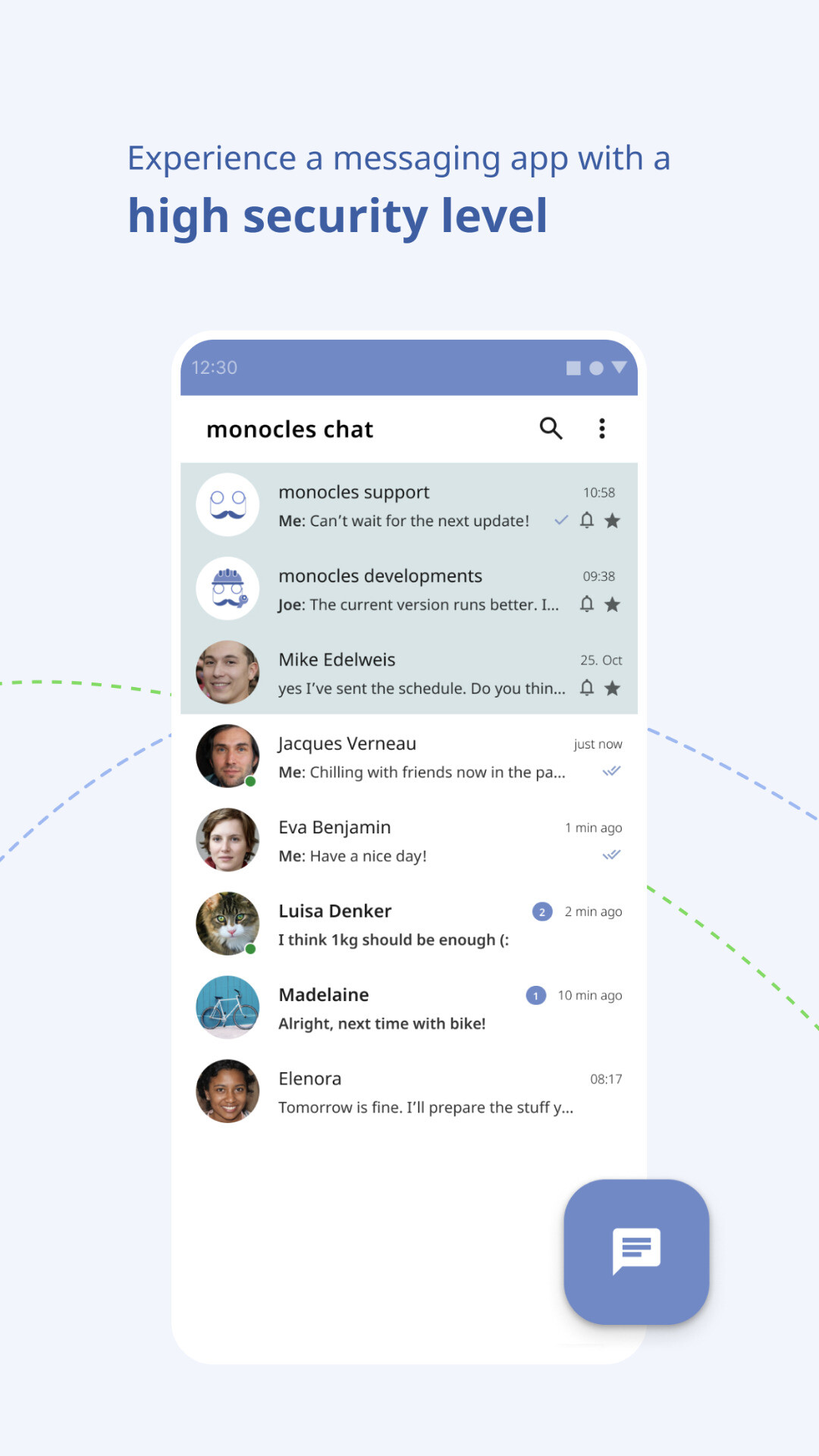

Monocles

Monocles is a very good fork of Conversations, with a few added features and better multi-account support.

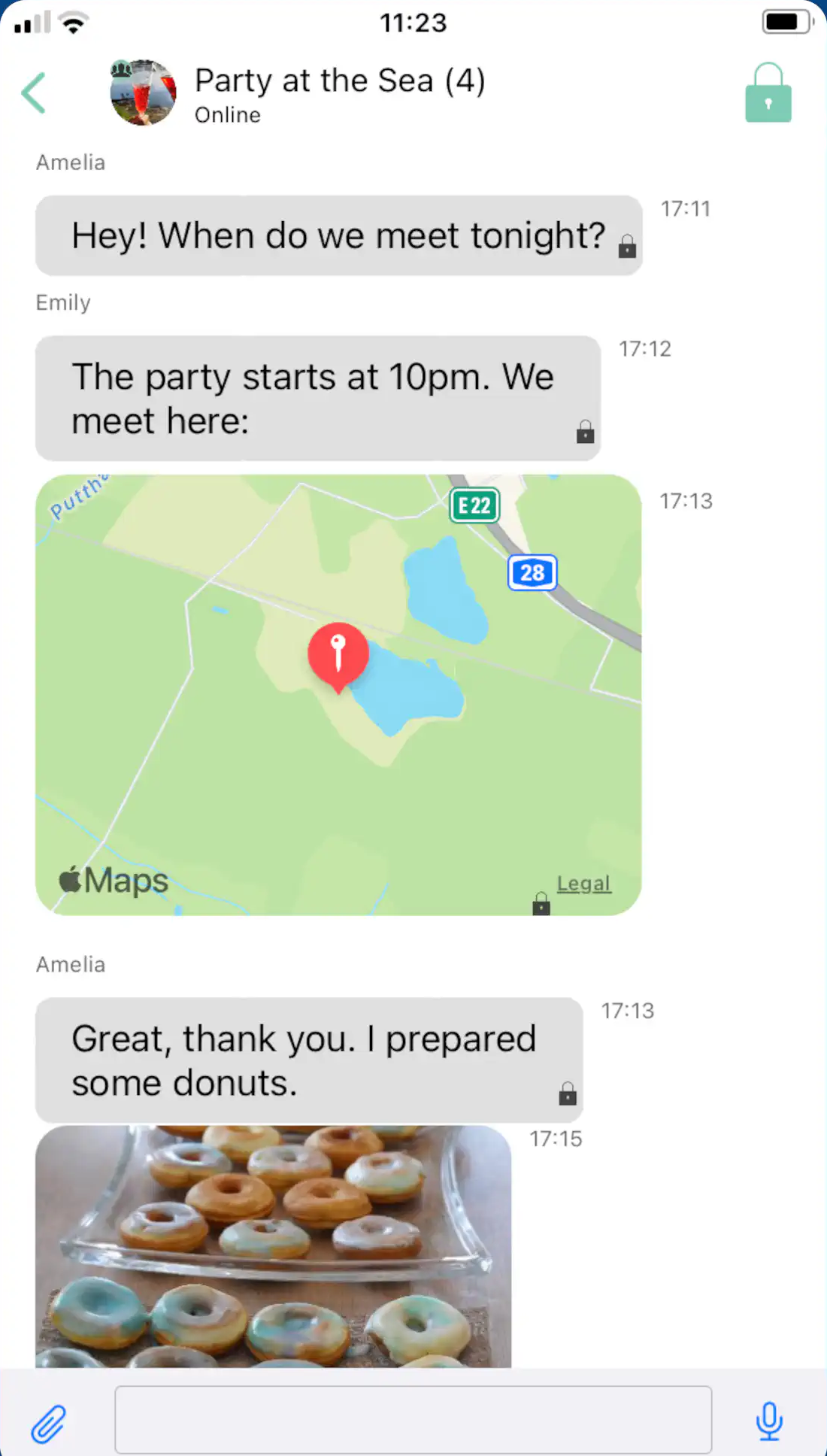

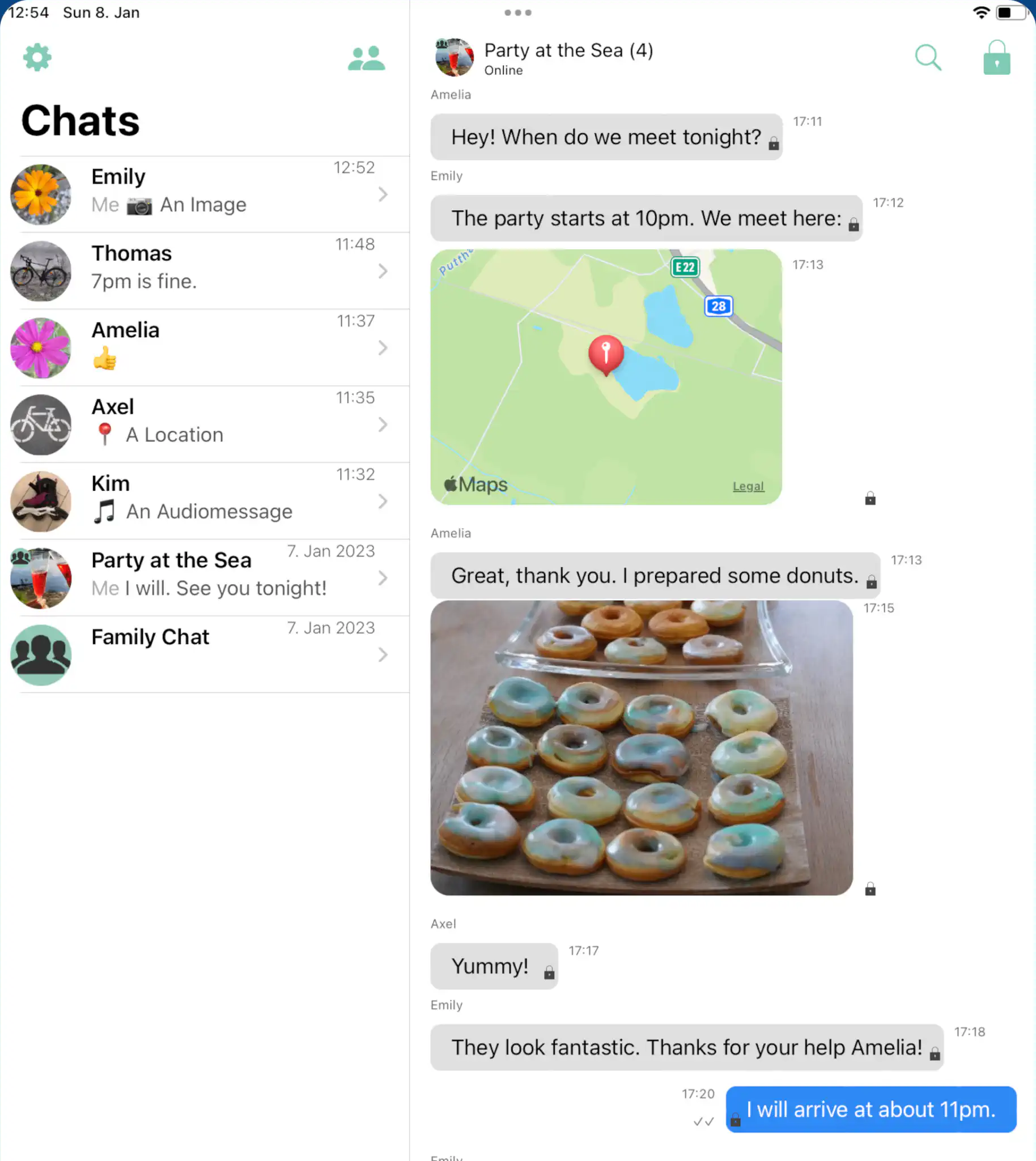

IOS and MacOS

Monal

I don’t use IOS or MacOS, but the best client for both appears to be Monal.

Windows and Linux

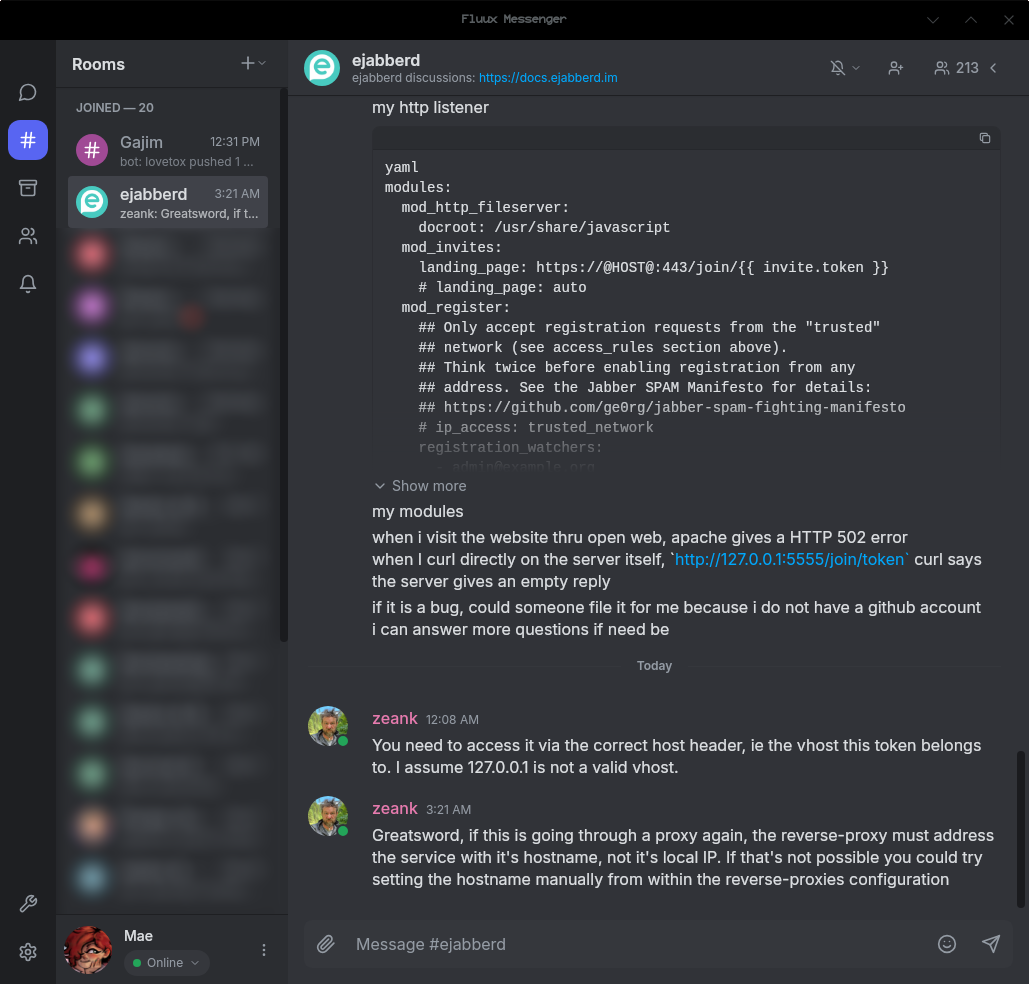

Fluux

Adding this after the original posting because wow. Fluux doesn’t yet support calling and isn’t quite as feature-complete as Gajim, but it’s close, it looks beautiful, and it’s like a month old! Seriously, the first commit to the git repo is from January! This January!

Bonus points: It’s built in rust—in Tauri, so pretty soon it’ll be available cross-platform! The current build is available for Linux, Windows, and MacOS, but I’ll bet Android and iOS are hot on the way.

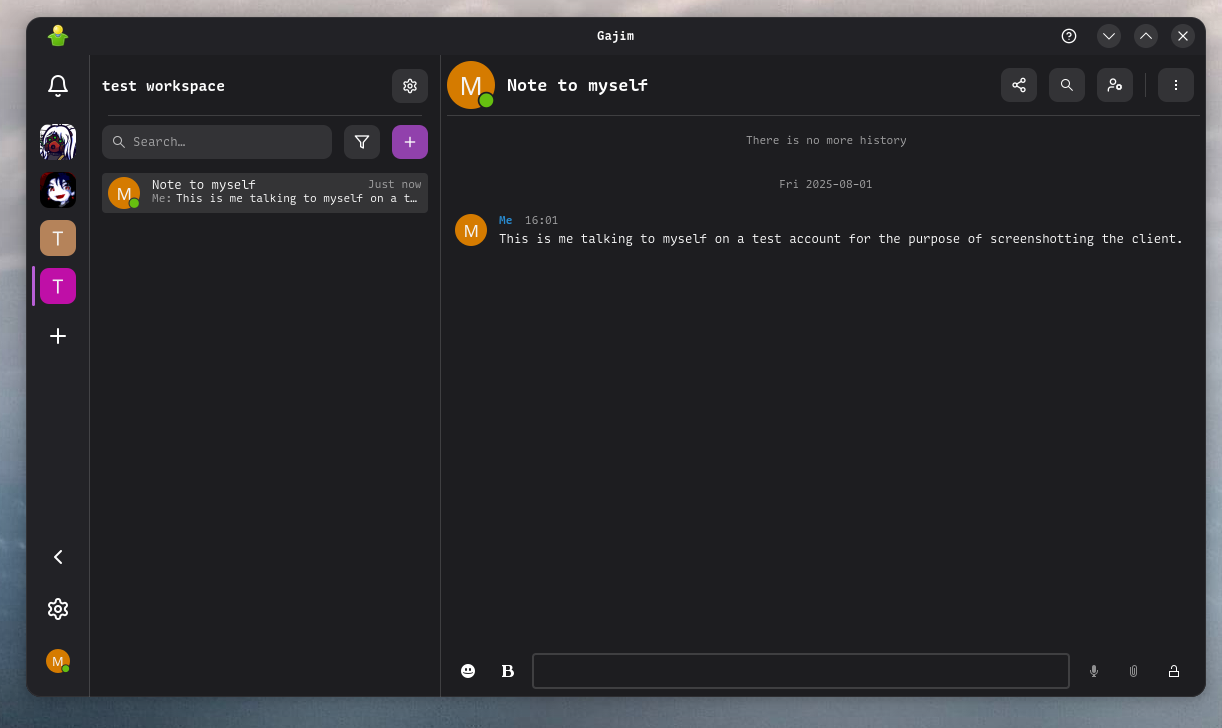

Gajim

Gajim has my favorite desktop UI, and is the most stable and feature-complete, except it doesn’t currently support calling.

It’s available for both Windows and Linux.

Dino

Dino supports calling, but is slightly less stable in my experience than Gajim, and I don’t like the UI as much.

It’s available on most Linux package managers, and there are unofficial Windows builds available, but the main app doesn’t have an official Windows build yet.

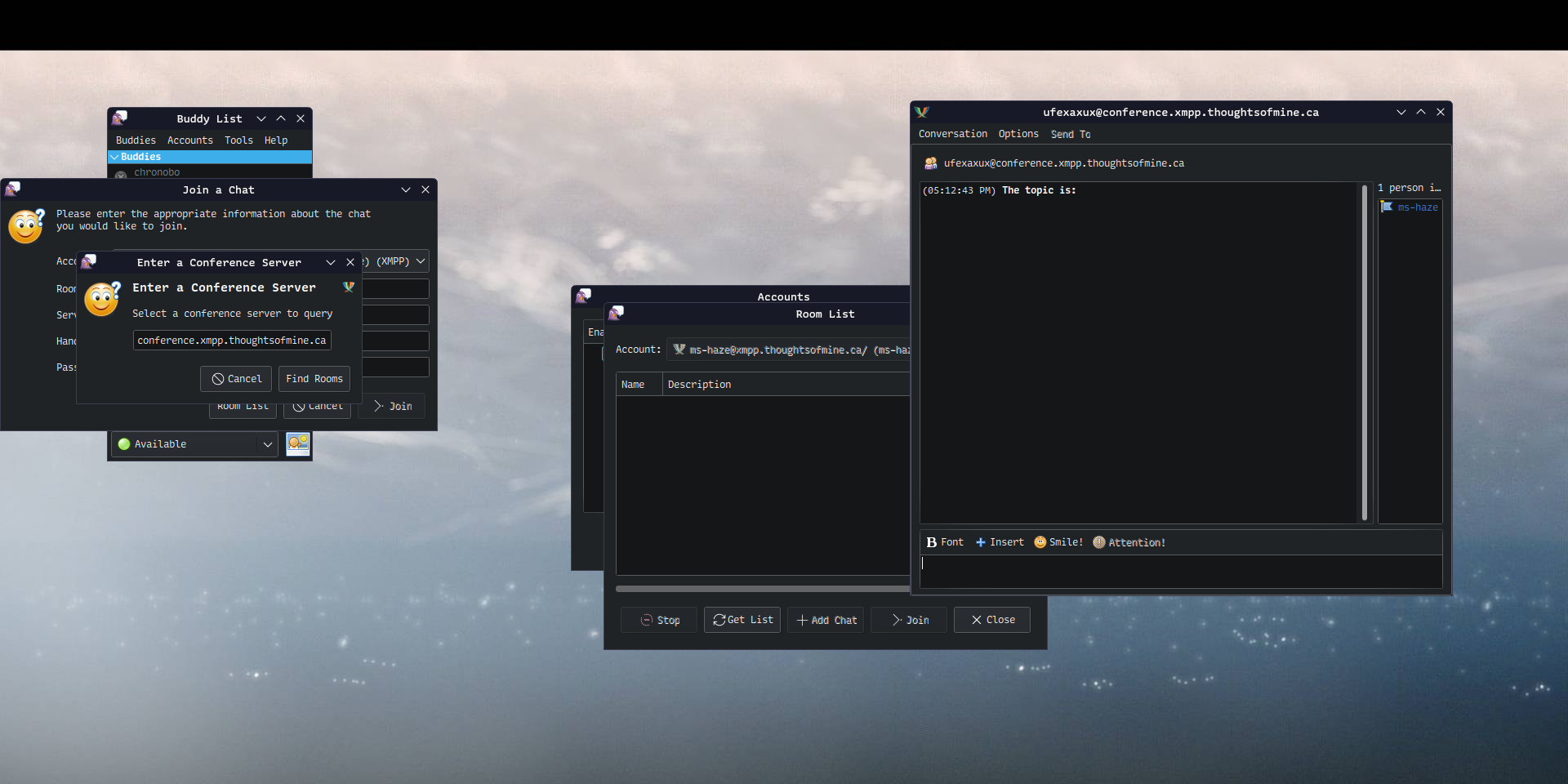

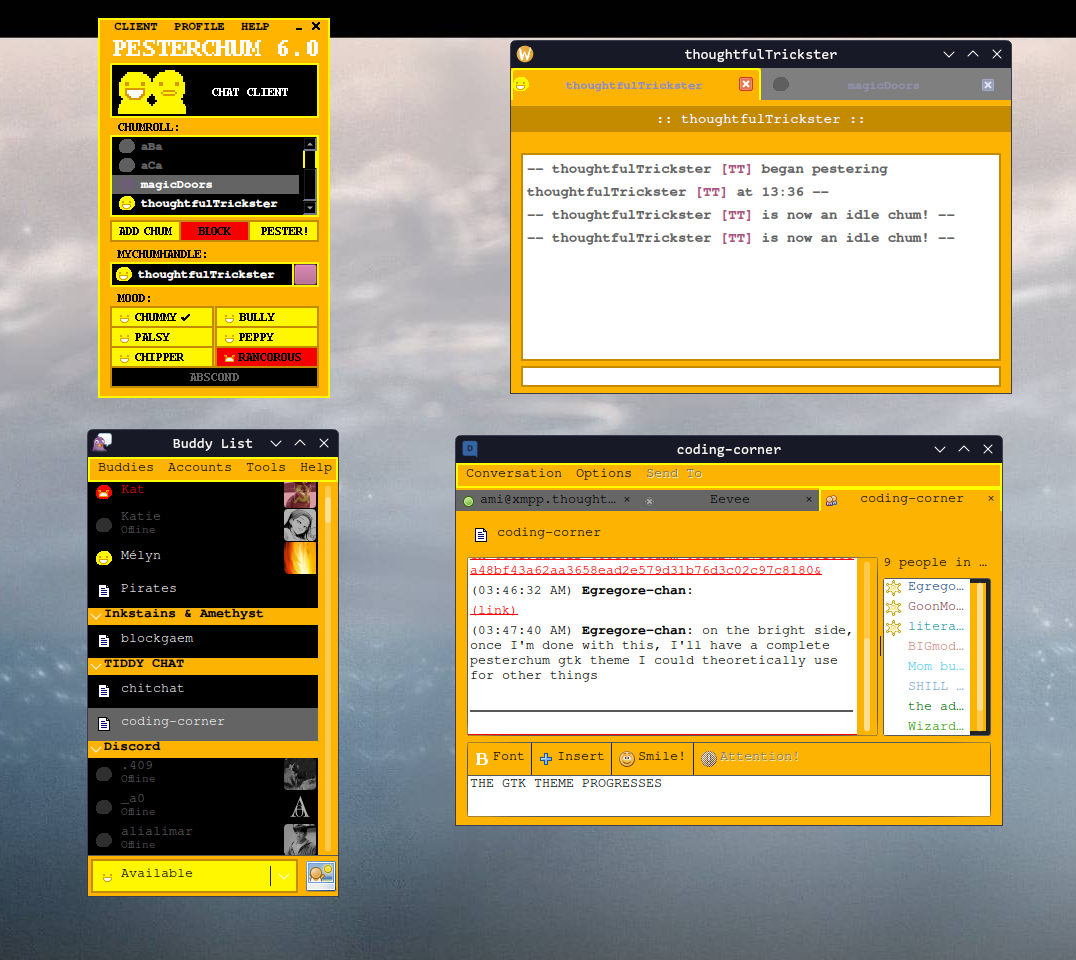

Pidgin

Pidgin looks like it came out in the early 2000s and doesn’t support the most widely-used encryption method without a plugin. However, it has support for a bunch of chat protocols, including Discord, which makes it easier to switch to.

It supports voice and video chat in XMPP, but potentially only on Linux.

It’s available for both Windows and Linux.

Plus, I was able to theme mine to look like Homestuck’s Pesterchum!

It does have a new version in the works, but that’s not fully functional yet, so keep an eye out for when it releases.

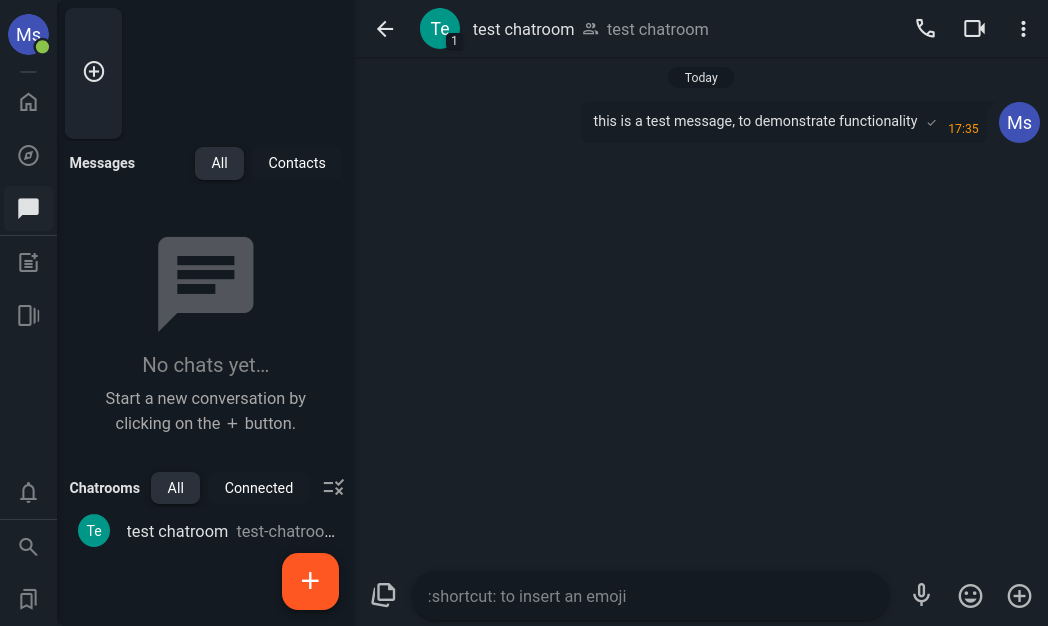

Web

Movim

Movim appears to be doing something interesting and trying to be an XMPP-based social media platform, with social blogging features.

It’s web-only, but it’s clearly trying new and interesting things, and it has the most modern UI out of probably every app here, so it’s probably worth checking out.

It does support calling.

Converse.js

Converse.js is a web-based client also available for desktop on Windows, Mac, and Linux.

It appears to be mostly feature-complete and doesn’t look bad, but I’m listing it last because web-based desktop applications are resource hogs and I don’t recommend them, and also because it doesn’t support calling.

That said, if you’re having problems with other clients, Converse.js is probably a decent fallback.

Conclusion

Ok, you’ve got an account, you’ve got a client: Go out there and connect! Get your friends to join, suggest it for the next group chat you need, and enjoy being free from corporate enshitification forevermore!

I know network effects are intimidating, and not everyone wants to up and join some new thing, but XMPP is good - better yet, it’s improving, unlike other platforms - and you can just do things! There are opportunities! Even if you can’t get an old group to switch, consider it the next time you or a friend is considering making a new one! It’s brighter and freeer over here, and I can’t wait for you to join me.

- See Matrix Notes by Anarcat.↑

- See also Matrix vs. XMPP by Luke Smith. Fair notice: I don’t endorse Luke Smith’s politics. His stances on technology are pretty good though.↑

Or: On the Value of Commonly-Maligned Emotions

The emotional electromagnetic spectrum, as written in the DC Comics superhero universe, is terrible and badly-written. There are like two emotions that aren’t evil, and those ones are perfect snowflakes that could never do anything wrong. Every other emotion is exclusively evil, and should not be trusted. 1 Love is on that list, by the way. And I don’t think they meant for their version of compassion to be awful? But it is.

This, uhh… fucking sucks.

So, here’s my take on the emotional electromagnetic spectrum.

Red: Rage

Rage is the emotion of those who have been wronged. When something is terrible and wrong and unfair, the bearers of Red light stare it in the face and scream no!

For as long as there is wrong in the world, there will be the rage of those who feel it and oppose it. Without rage, the wrong goes unrighted, and the wronged continue to be wronged.

At its worst, rage is senselessly beating against the world, flailing against the injustices and hurting anything you can.

At its best, rage means seeing all that is wrong in the world and tearing it out at its root, protecting all that wrong harms at your back.

Orange: Avarice

Avarice is the emotion of those who have gone without—the emotion of those who need. It is the urge, when you find something important, to take it and keep it, safe from all who would harm it or take it away. Avarice is about knowing how you want the world to be shaped, and needing to make it that shape. Avarice is the emotion of protectors: It drives us to keep what we love safe, and what makes us reach far into the heavens for our goals.

At its worst, avarice means desperately clutching things so close to you that they crumble, and never letting go of that which is not, or should not be ours.

At its best, avarice means fighting to get what we need, cherishing what is ours, and protecting it with all we have.

Yellow: Fear

Fear is the emotion of the wary. When something is precarious, fear is what keeps us alert and focused, ready to respond the moment things go wrong.

At its worst, fear means quaking at every sudden movement or sharp sound, even when all is right—it means preparing forever, at the cost of the ability to allow or appreciate those things we are afraid of losing.

At its best, fear means holding onto and appreciating that which we are afraid to lose—being ever-ready and ever-prepared for something to go wrong, and to spring into action and protect it.

Green: Will

Will is the emotion of the committed. It is the emotion of those who strive and those who continue to strive, no matter how hard the journey becomes. Will is our drive and ambition to carve the world we want out of solid steel if we have to.

At its worst, will means controlling others, enforcing your will against them and substituting their will for your own.

At its best, will means unceasingly working for what you and others want, in spite of any and all opposition.

Blue: Hope

Hope is the emotion of the downtrodden. It is the belief that no matter how bad things get, they can always become better. Hope gets us through our darkest days, and sees us through the other side. Hope is the possibility that can never be destroyed.

At its worst, hope means believing, against all reality, that things will get better, and letting that hope deter you from making it so.

At its best, hope means staying strong in the face of hardship, and knowing that things can always get better. It is seeing your house burned down, and knowing that eventually, you can rebuild it.

Indigo: Compassion

Compassion is the emotion of those who have been to a dark place, and come out the other side with understanding for anyone else who is suffering. Compassion is the emotion of those who have done wrong, and know what it is like to be someone who does wrong—of those who have felt pain, and know that none of us deserve it.

At its worst, compassion means letting those who have harmed you harm you again and again, because you understand why they do it.

At its best, compassion means lifting those who have hurt you out of the darkness, and making them into the people they deserve to become, and who you deserve to live amongst.

Violet: Love

Love is the emotion of those who have been alone. In its purest form, it is the desire and need for another person, and for the well-being of that person. Love is not the fear of losing someone, or the avarice of attachment. It is not the compassion of understanding. Love is valuing another being, not for who or what they could become but for who they are.

At its worst, love means taking someone, keeping them from any else who could love them, and never letting them leave your sight. It is the worst of many other emotions, bundled together and tied around another.

At its best love means wanting the best for someone, no matter what. It means cherishing them not for who or what they could become, but for who they are. It means protecting them from all that could harm them, and making a better world for them, because they deserve one.

Grey: Sorrow

Sorrow is the emotion of those who have lost. It is the emotion of those who know that the world is not right, and that horrible things are happening, and who choose to accept that reality and to keep going. Sorrow is about seeing the horror and pain of the world, and refusing to look away or hide. Without sorrow, there is no acceptance.

At its worst, sorrow means giving up. It means wallowing in the pool of infinite sorrow and deciding that nothing will ever be good again.

At its best, sorrow means grieving. It means bathing in the pool of infinite sorrow and coming out of it with resolve and understanding.

Conclusion

Ok, so what is this for?

Well, you absolutely can (and I might) use it to write Green Lantern fanfiction with much more interesting worldbuilding than the original, but that isn’t the primary thing I meant this for when I was thinking about it.

No, when this caught my eye and bothered me enough to write my own version, I was thinking about it as a way of thinking about types of people, and what drives them. 2 Partly inspired by Duncan Sabien’s conceptualization of the MTG Color Wheel as an intuition pump for understanding people.

A person can have any number of these colors, but they tend to be primarily driven by one or two. For instance, you might know someone who is primarily driven by their knowledge and guard of their own desires (Yellow), or someone who is driven to do what must be done because it must be done (Green), but you also might know someone who is primarily driven by multiple of these emotions, like fear and hope, or love and compassion.

There are many different ways to express these colors, but I think it’s still an interesting and useful way of conceptualizing people, and naming a part of how they work.

It’s important that every emotion listed here can be both positive and negative. No emotion is solely evil, and none is solely good. The DC conception of this system is offensive to me because it places a normative judgement on each of its colors, where, in reality, each of them serves a purpose.

I wrote this post in a righteous fervor, after reading a wiki article on the Emotional Electromagnetic Spectrum and being heavily disappointed. I hope it’s useful to you.

- Love is on that list, by the way. And I don’t think they meant for their version of compassion to be awful? But it is.↑

- Partly inspired by Duncan Sabien’s conceptualization of the MTG Color Wheel as an intuition pump for understanding people.↑

Or: Please, I’m Begging You: Stop Copying D&D

Note: This is a cross-post from the Quarterstaff Quarterly zine. Go check it out!

I’ve played a good number of roleplaying games, and one thing I’ve consistently noticed is that d20 action resolution is the worst.

Have you ever spent 5 turns missing an enemy, even though your Attack Bonus is 6 points higher than their Armor? Ever rolled a 1 and failed a check your character should be an expert at?

Automatic failure on 1 and success on 20, as in D&D, definitely make this method worse, but even in systems without those mechanics, d20 is very rarely the best option for any particular job.

I’m going to look at a number of alternate forms of random choice and action resolution in roleplaying games, and explain what makes each one great—and more importantly, explain where and how they’re best used.

Other 1dX Methods (1d10, 1d12, etc.)

No! Bad! This is just d20 but with smaller dice!

Seriously though, while flat die randomness can be the correct option sometimes (such as when rolling for equally-likely random events on a table), it is used far more often than it is welcome.

Next!

3d6

Now we’re talking!

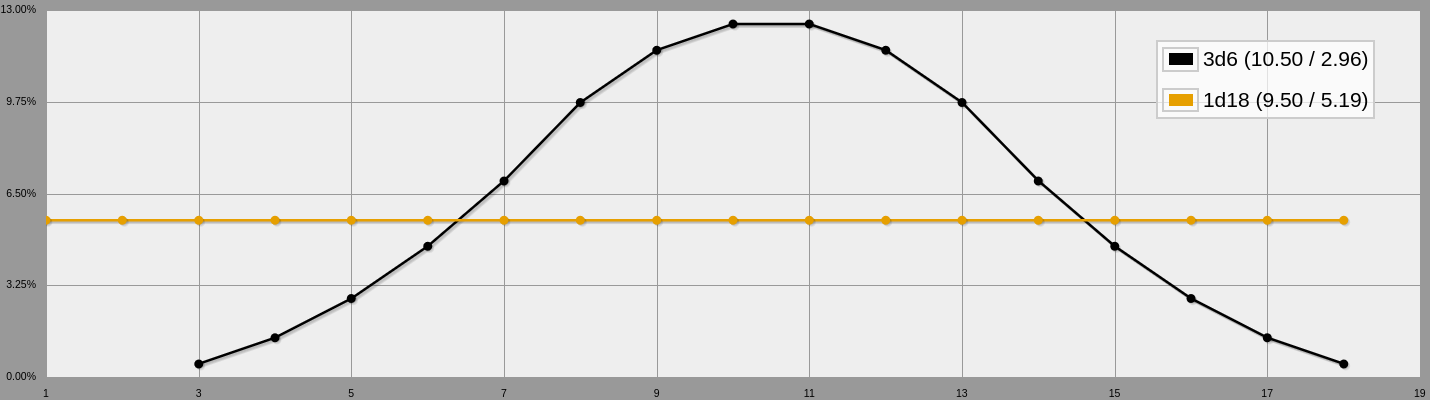

“But Mae,” you might ask, “isn’t this just the same as 1d18?”

No! 3d6 (and similar systems) have one major advantage against 1dX: They’re weighted.

When you roll an action resolution check (an attack, for instance), the result will be weighted towards your skill/attribute level! This means that, instead of a point in a modifier moving the range of possibilities up, it moves the distribution up!

Not only is it weighted, it’s (approximately) a bell curve, which is likely to be a realistic distribution-of-outcomes for most real-world situations a die roll might be modelling!

There’s a reason D&D players classically roll 3d6 for stats instead of 1d20.

Dice Pools

Dice pools are when, instead of the modifier for the dice changing, the number of dice changes. You roll a number of dice (generally d6s), and then sum up how many of a certain result (or set of results) appear, and that’s your roll.

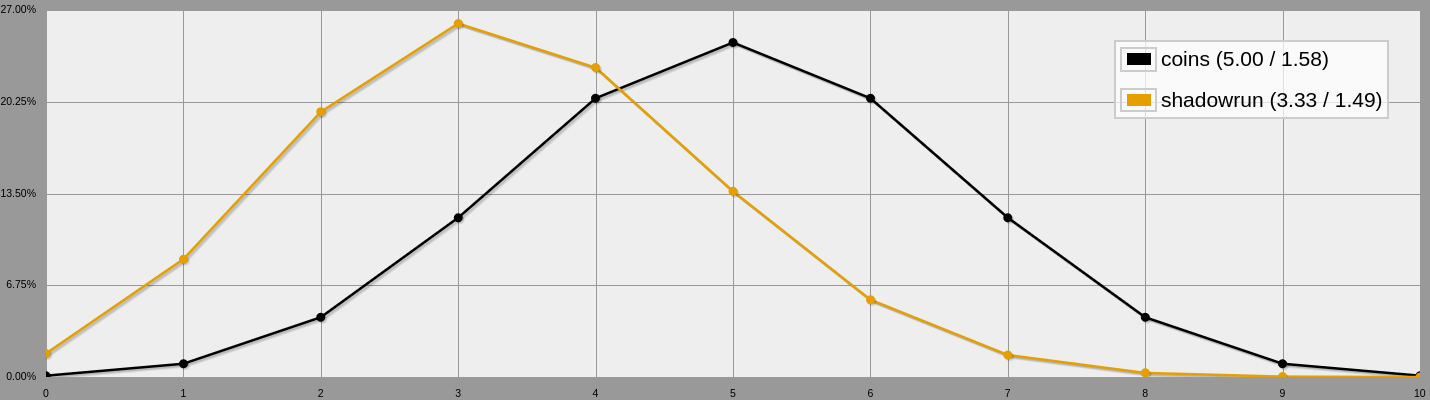

So, for instance, in Shadowrun 5e, you might roll a dice pool of (for example) 7d6, count up how many of those dice show a 5 or a 6, and that’s your “hits”. In that system, you also keep track of how many 1s are rolled, and if it’s more than half the dice you rolled, it’s a “glitch” (a bit like a Critical Failure in a d20 system).

This sort of system is interesting, because it has a similar sort of clustering to 3d6, except the clustering is tighter, and you can skew the location of the cluster by changing which values are counted: With the Shadowrun dice pool, a 10-die pool will be most likely to roll around 3 hits, but with a variation counting 4, 5, and 6 (or using coins), it’s most likely to roll around 5 hits.

Another interesting attribute of this system is that it has a minimum outcome of zero. Most dice-based resolution systems will have a minimum outcome equal to the number of dice rolled, but that isn’t true for dice pools!

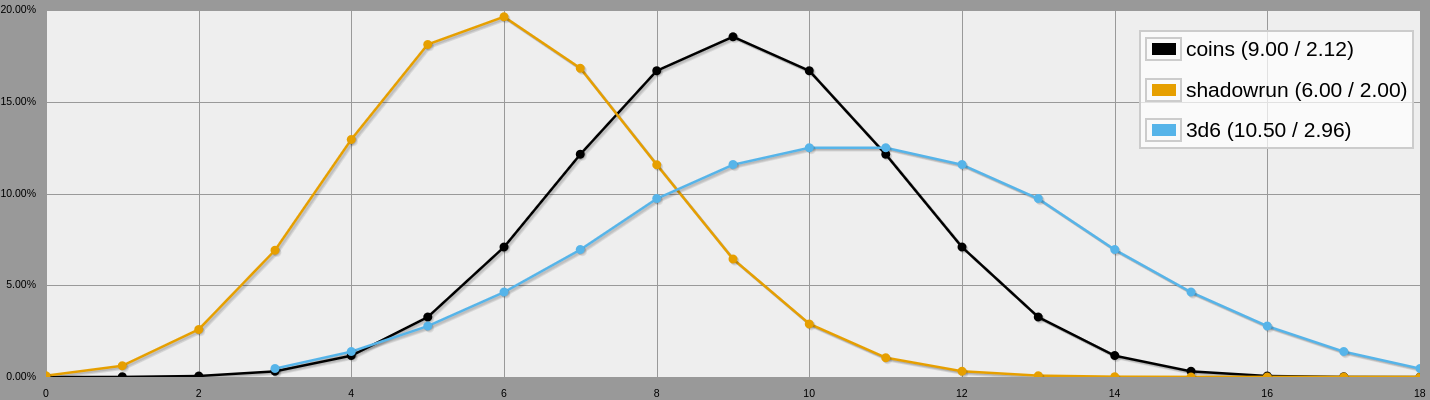

Comparing 18-die pools to a 3d6 roll, you can really see how tight the clustering is:

Dice pools also have the advantage that they don’t use uncommonly-sized dice: most non-roleplaying tabletop and board games use d6s, so most households will have a large number of them laying around already. This sets the bar for entry noticeably lower than systems that use other polyhedral dice!

Dice pool systems are most often used for combat situations, and tend to work best in systems and situations with smaller numeric ranges (you wouldn’t want to be rolling Shadowrun hit dice for an enemy with hundreds of hit points, no matter how many dice you were given). Adding one die in a dice pool system means adding a fraction of a point on average, which means you can give more granular bonuses more easily.

Cards

Ok, now cards are very interesting. Dice pools are pretty different from other dice systems, but that’s nothing compared to cards!

The most interesting difference between cards and dice is, of course, that the probability of different outcomes can change every time you draw one. Drawing a card from a deck means that card (or that copy of that card, if you’re using a type of deck with duplicates) won’t be drawn again until you reshuffle.

Interestingly, this property means that card-based randomness is a case in which gambler’s fallacy (the fallacy by which people think that their chances of success increase with each failure) is mostly true, which can make these systems feel more intuitive for some people—nobody likes to roll a 1 three times in a row, and if you use playing cards, you can make that impossible!

Card-based randomness can work a lot of different ways, from numbered cards as an interesting replacement for dice, to random events drawn from a deck (as in Wretched & Alone), to ability decks (as in GrimoirePunk), to who-knows-what-else 1 Gun & Slinger apparently uses both Go Fish and Blackjack as action resolution mechanisms. , with per-player decks or shared decks between players or even shared decks between players and enemies! The sky’s the limit, and you absolutely should experiment with card-based randomness the next time you’re designing or homebrew-modding a system.

Points

Why do you need randomness at all?

The Marvel Universe Roleplaying Game (not to be confused with the Marvel Multiverse Roleplaying Game) doesn’t contain randomness in any form. Instead, characters have an Energy pool which they can take from to perform actions. When a player wants to perform an action, they guess how hard their character will need to try, in order to succeed at the action. They then spend that much energy, and the GM determines whether or not they succeeded based on the difficulty and how much they spent (or how much they spent vs how much their opponent spent, for contested checks). Levels in abilities can increase the maximum energy a player can spend on an action, or occasionally add free bonus energy to an action.

This system makes actions’ outcomes depend entirely on player choice, gives players the option of increasing their odds of success at the cost of a limited (but regenerating) resource, and completely removes the problem of unlikely rolls causing otherwise-competent characters to randomly fail at tasks they’ve spent their lives mastering.

Other point-based diceless systems exist, but I haven’t played them!

Jenga

Yeah, that’s right, Jenga! Anything can be an action-resolution mechanic if you try hard enough!

The Wretched & Alone system and the Dread roleplaying game both use a Jenga tower to resolve actions: When you perform a risky action, you pull a block from the tower. If you pull it out successfully, you succeed; if the tower falls, you die.

This is a great system for narrative systems with high mortality rates, and can really up the tension, but is a really bad bet for any other sort of system. Its biggest weaknesses are that it’s necessarily pass/fail, and that failure basically has to be really final, or else you’re setting up a Jenga tower repeatedly during the game, and that takes a while and kills the tension. Every other system mentioned here can have degrees of success or failure, but Jenga towers basically have to be pass/fail, and that only really lends itself to some sorts of game.

Still, if you’re making the right sort of game, you absolutely should consider trying this out—it can be a lot of fun!

Conclusion

There are a ton of different sources of randomness and action-resolution for roleplaying games, and a ton of space for exploration and improvement! You absolutely both can and should experiment with different options when designing or modifying systems. Just remember to playtest, to make sure things are actually fun! Now go fourth and write better roleplaying games!

- Gun & Slinger apparently uses both Go Fish and Blackjack as action resolution mechanisms.↑