Or: Please, I’m Begging You: Stop Copying D&D

Note: This is a cross-post from the Quarterstaff Quarterly zine. Go check it out!

I’ve played a good number of roleplaying games, and one thing I’ve consistently noticed is that d20 action resolution is the worst.

Have you ever spent 5 turns missing an enemy, even though your Attack Bonus is 6 points higher than their Armor? Ever rolled a 1 and failed a check your character should be an expert at?

Automatic failure on 1 and success on 20, as in D&D, definitely make this method worse, but even in systems without those mechanics, d20 is very rarely the best option for any particular job.

I’m going to look at a number of alternate forms of random choice and action resolution in roleplaying games, and explain what makes each one great—and more importantly, explain where and how they’re best used.

Other 1dX Methods (1d10, 1d12, etc.)

No! Bad! This is just d20 but with smaller dice!

Seriously though, while flat die randomness can be the correct option sometimes (such as when rolling for equally-likely random events on a table), it is used far more often than it is welcome.

Next!

3d6

Now we’re talking!

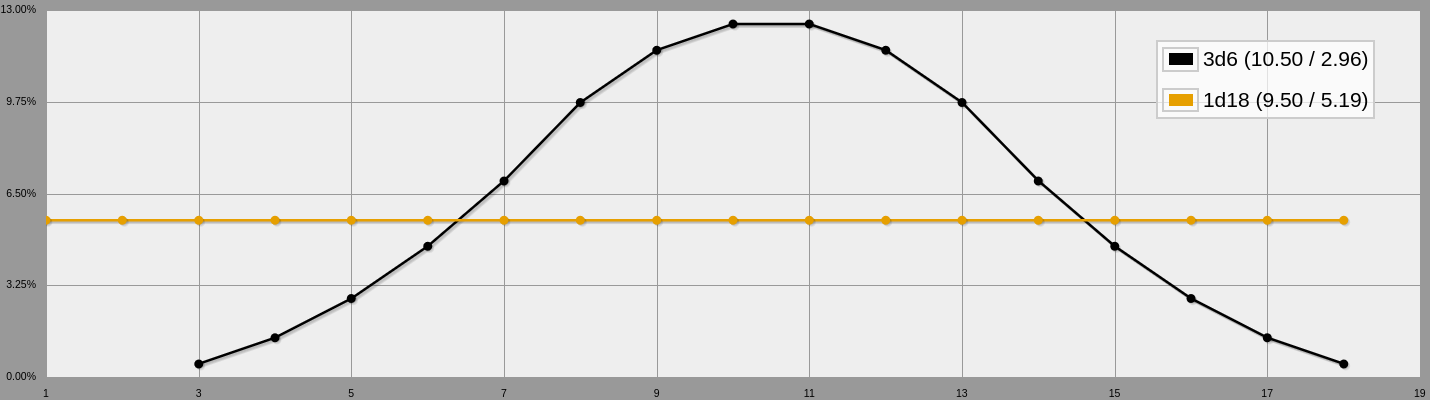

“But Mae,” you might ask, “isn’t this just the same as 1d18?”

No! 3d6 (and similar systems) have one major advantage against 1dX: They’re weighted.

When you roll an action resolution check (an attack, for instance), the result will be weighted towards your skill/attribute level! This means that, instead of a point in a modifier moving the range of possibilities up, it moves the distribution up!

Not only is it weighted, it’s (approximately) a bell curve, which is likely to be a realistic distribution-of-outcomes for most real-world situations a die roll might be modelling!

There’s a reason D&D players classically roll 3d6 for stats instead of 1d20.

Dice Pools

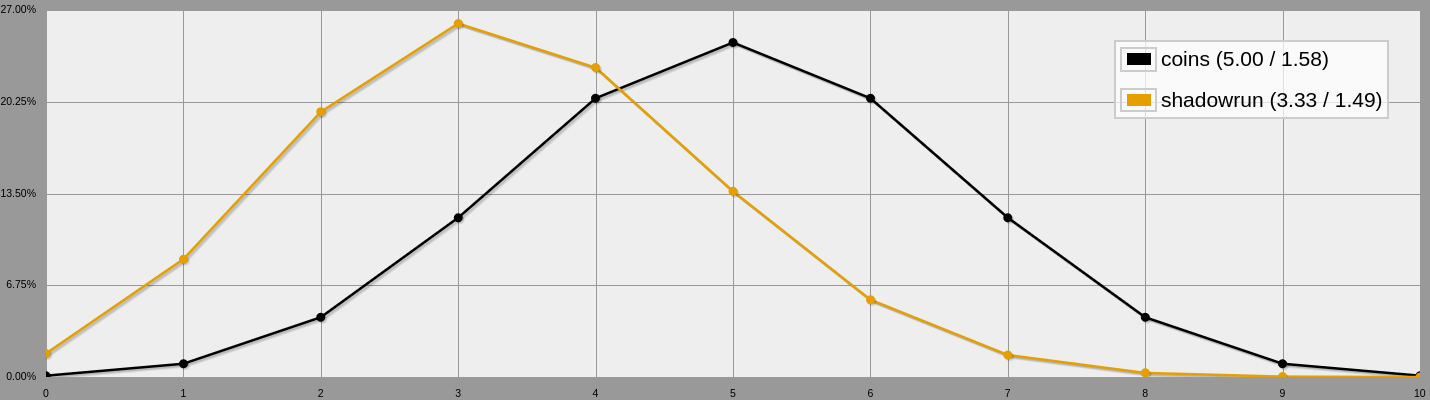

Dice pools are when, instead of the modifier for the dice changing, the number of dice changes. You roll a number of dice (generally d6s), and then sum up how many of a certain result (or set of results) appear, and that’s your roll.

So, for instance, in Shadowrun 5e, you might roll a dice pool of (for example) 7d6, count up how many of those dice show a 5 or a 6, and that’s your “hits”. In that system, you also keep track of how many 1s are rolled, and if it’s more than half the dice you rolled, it’s a “glitch” (a bit like a Critical Failure in a d20 system).

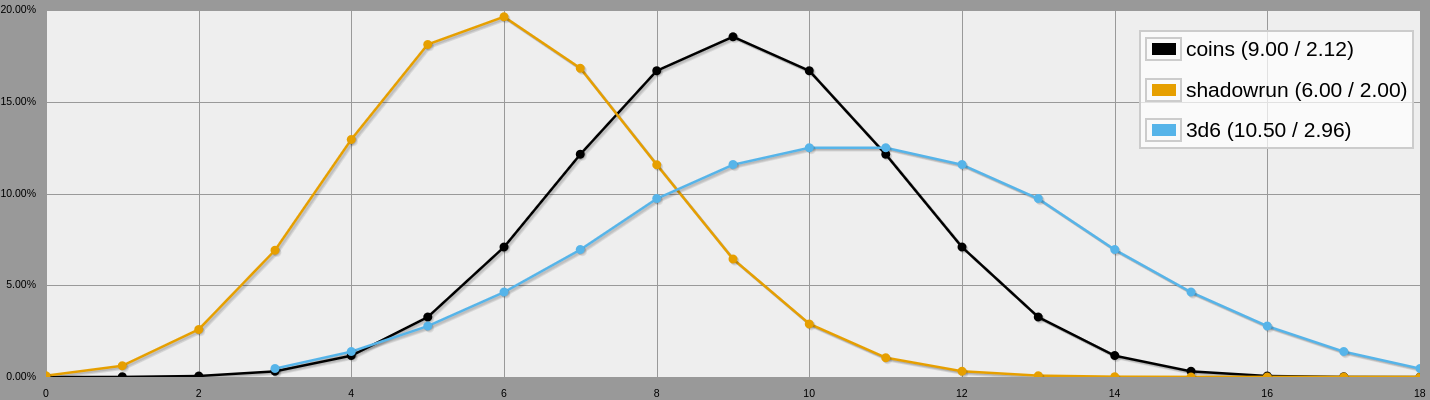

This sort of system is interesting, because it has a similar sort of clustering to 3d6, except the clustering is tighter, and you can skew the location of the cluster by changing which values are counted: With the Shadowrun dice pool, a 10-die pool will be most likely to roll around 3 hits, but with a variation counting 4, 5, and 6 (or using coins), it’s most likely to roll around 5 hits.

Another interesting attribute of this system is that it has a minimum outcome of zero. Most dice-based resolution systems will have a minimum outcome equal to the number of dice rolled, but that isn’t true for dice pools!

Comparing 18-die pools to a 3d6 roll, you can really see how tight the clustering is:

Dice pools also have the advantage that they don’t use uncommonly-sized dice: most non-roleplaying tabletop and board games use d6s, so most households will have a large number of them laying around already. This sets the bar for entry noticeably lower than systems that use other polyhedral dice!

Dice pool systems are most often used for combat situations, and tend to work best in systems and situations with smaller numeric ranges (you wouldn’t want to be rolling Shadowrun hit dice for an enemy with hundreds of hit points, no matter how many dice you were given). Adding one die in a dice pool system means adding a fraction of a point on average, which means you can give more granular bonuses more easily.

Cards

Ok, now cards are very interesting. Dice pools are pretty different from other dice systems, but that’s nothing compared to cards!

The most interesting difference between cards and dice is, of course, that the probability of different outcomes can change every time you draw one. Drawing a card from a deck means that card (or that copy of that card, if you’re using a type of deck with duplicates) won’t be drawn again until you reshuffle.

Interestingly, this property means that card-based randomness is a case in which gambler’s fallacy (the fallacy by which people think that their chances of success increase with each failure) is mostly true, which can make these systems feel more intuitive for some people—nobody likes to roll a 1 three times in a row, and if you use playing cards, you can make that impossible!

Card-based randomness can work a lot of different ways, from numbered cards as an interesting replacement for dice, to random events drawn from a deck (as in Wretched & Alone), to ability decks (as in GrimoirePunk), to who-knows-what-else 1 Gun & Slinger apparently uses both Go Fish and Blackjack as action resolution mechanisms. , with per-player decks or shared decks between players or even shared decks between players and enemies! The sky’s the limit, and you absolutely should experiment with card-based randomness the next time you’re designing or homebrew-modding a system.

Points

Why do you need randomness at all?

The Marvel Universe Roleplaying Game (not to be confused with the Marvel Multiverse Roleplaying Game) doesn’t contain randomness in any form. Instead, characters have an Energy pool which they can take from to perform actions. When a player wants to perform an action, they guess how hard their character will need to try, in order to succeed at the action. They then spend that much energy, and the GM determines whether or not they succeeded based on the difficulty and how much they spent (or how much they spent vs how much their opponent spent, for contested checks). Levels in abilities can increase the maximum energy a player can spend on an action, or occasionally add free bonus energy to an action.

This system makes actions’ outcomes depend entirely on player choice, gives players the option of increasing their odds of success at the cost of a limited (but regenerating) resource, and completely removes the problem of unlikely rolls causing otherwise-competent characters to randomly fail at tasks they’ve spent their lives mastering.

Other point-based diceless systems exist, but I haven’t played them!

Jenga

Yeah, that’s right, Jenga! Anything can be an action-resolution mechanic if you try hard enough!

The Wretched & Alone system and the Dread roleplaying game both use a Jenga tower to resolve actions: When you perform a risky action, you pull a block from the tower. If you pull it out successfully, you succeed; if the tower falls, you die.

This is a great system for narrative systems with high mortality rates, and can really up the tension, but is a really bad bet for any other sort of system. Its biggest weaknesses are that it’s necessarily pass/fail, and that failure basically has to be really final, or else you’re setting up a Jenga tower repeatedly during the game, and that takes a while and kills the tension. Every other system mentioned here can have degrees of success or failure, but Jenga towers basically have to be pass/fail, and that only really lends itself to some sorts of game.

Still, if you’re making the right sort of game, you absolutely should consider trying this out—it can be a lot of fun!

Conclusion

There are a ton of different sources of randomness and action-resolution for roleplaying games, and a ton of space for exploration and improvement! You absolutely both can and should experiment with different options when designing or modifying systems. Just remember to playtest, to make sure things are actually fun! Now go fourth and write better roleplaying games!

- Gun & Slinger apparently uses both Go Fish and Blackjack as action resolution mechanisms.↑